The State of Game Studio Financing

How to think about investing in and fundraising for game studios in a capital-constrained environment.

VCs disrupted publisher-based studio financing. Now VCs and publishers must adapt to a changing macro-political landscape and disrupt themselves.

The current state of the games industry was looking bleak for quite a while last year. Several layoffs at Riot, Unity, Activision Blizzard, Discord, and more recently Take-Two have had chilling effects on the industry while games VC financing for the industry has returned to pre-pandemic levels (see chart from Pitchbook below). However, remember that many of the greatest tech companies were created during market downturns: Uber, Airbnb, Slack, Whatsapp, Square, Venmo. We believe the same will be the case here. Zig, when others zag.

There is hope in the market now too; Konvoy just reported the first uptick in venture financing for games in 9 quarters. At a16z we just announced our $600M GAMES FUND TWO; Bitkraft has raised a $275M Fund III; PlayVentures has raised at least $78M for their third fund; and there are new funds like Laton Ventures that are coming on to the market too. That’s not to say the financing market for studios will be easy. Founders who raised in 2021-22 will be coming into a market that’s much different than the ZIRP (zero-interest rate phenomenon) environment of 2021 when money was more freely flowing. That’s because interest rates impact the opportunity cost of capital (among many other factors: venture debt, velocity of money, inflation, etc.). Investors during the ZIRP era were looking for more risk-on assets to deploy capital into because the threshold for returns is so low; investors have to take risks otherwise their cash is depreciating due to inflation. But when interest rates are high, investors tend to go risk-off because the opportunity cost is much higher, such as investing in stable T-bills returning 4-5% per annum.

This dynamic particularly affects games. Because games take so long to bake and there’s not a ton of signal gained during that process, the capital at stake is considered quite risky and illiquid over a long period of time. Building a consumer mobile app might cost several hundred thousand dollars or less to full launch (a few good engineers hacking at it for a few months), but a game, to build just a MVP, could take at least a year of ten or so talented artists, engineers, and developers building the concept and often costing several million dollars.

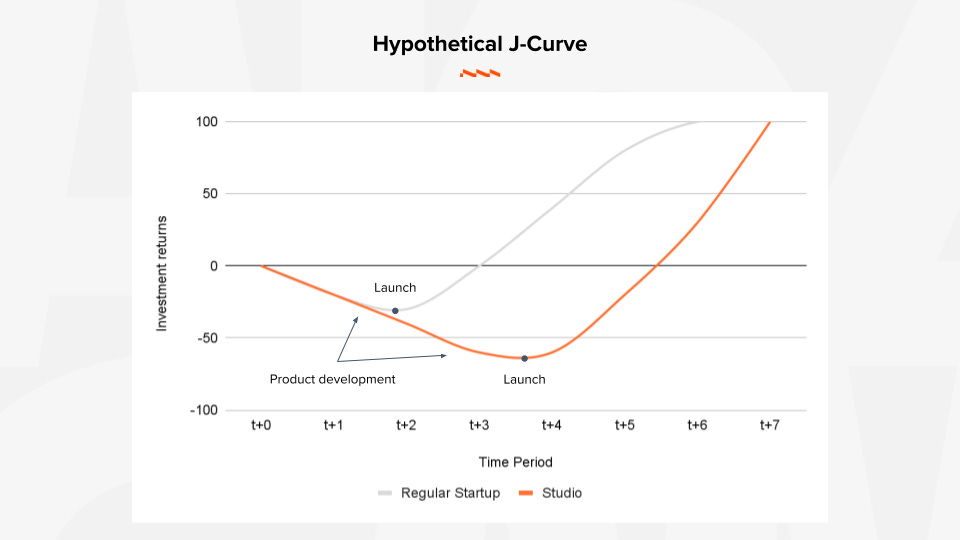

To illustrate this, the best example is the J-curve. The concept applies to many things, from careers to investments to global trade. For venture capital and startups, it’s the amount of capital that needs to go into the startup before you start seeing glimmers of hope and product-market fit. For a studio, not only is the time to market longer, but also the capital required and the time horizon. This also affects investor IRR (internal rate of return) potentially, since the time needed to return capital is longer. It’s also why, in my opinion, VCs might be more excited about crypto games, because they have faster time to liquidity (tokens) and more options for earlier monetization (NFTs) from a very practical standpoint.

It’s similar to biotech or hard-tech investments, where the investment and time horizon is quite a bit higher, but the problem with games is that they don’t quite have the same moats as other products. With biotech you have patents; with hardware you have proprietary IP and physical capex (factories). There are also alternative financing and acquisition options with pharma snapping up promising preclinical drugs and governments granting large contracts to R&D products. With games, you’re competing for consumer attention that’s split among apps, videos, music, and more. That’s why investors are always looking for differentiators with games: faster GTM, cheaper UA, network effects, platform plays, UGC lock-ins.

One thing I’ve been debating in particular is what the moat for a game could be. Player liquidity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a multiplayer game that has differing skill expression, but it’s not a true network effect per se. With a ridesharing app like Uber, every additional driver reduces potential wait times for riders, incentivizing more riders to use the app which in turn draws in more drivers. But for games, after you hit a certain threshold of players then I’m not sure additional players are additive for enjoyment. There are a few moats that I’ve been thinking about:

UGC is clearly a two-sided marketplace moat. More players incentivizes more creators which makes the platform more valuable for those players. But getting the high quality creators that create the best experiences is the most important thing.

UA could be a moat, if your LTVs are just better than other competitors, so you can bid and win better inventory and get the highest spending players.

Creator content and communities could be a moat. The more players that create content on YouTube, TikTok and other social platforms for a game, the more enjoyable it is to partake in that community vs. other games. But I’m not sure how defensible this is over time. That being said, strong social bonds and guilds can definitely be a moat (think of the corporations in EVE Online and how persistent they are).

Game specific-knowledge could be a moat. It’s harder to swap from League to DOTA because you have to relearn all the specific champions and mechanics, whereas it’s much easier to swap from CS to Valorant since a lot of the core movement and aim mechanics transfer over.

Okay, so we talked about some of the dynamics of the market and game studio investing. In the following sections of this essay, I want to share my opinion on what investors are looking for, and propose some ideas for how to think about studio financing.

The core questions that investors are thinking about at each milestone for a game are:

Seed: Is this the best team to tackle the opportunity and will they be able to get enough capital to get this game to market? Is the pitch differentiated enough and are they riding some sort of market tailwind that will allow them to become a venture-scale outcome? Have they thought through all the important company building parts: product, engineering, GTM, talent, and BD?

Series A: What’s your production velocity and how much have you shipped? What does the team still need to prove about the core game thesis? Can you get to at least an open beta with this tranche of capital, and is this playable the top 1% that we’ve seen this year?

Series B: This will likely be a post-launch round. There might be a non-dilutive publishing round after the Series A, but generally growth investors are investing against metrics rather than ideas. As such, they’ll be asking for the game metrics: D1 / 7 / 30 retention, DAU/MAU, LTV:CAC, CPIs, ARPU, ARPDAU. Is the game on the path to becoming a $B franchise and how will they scale the studio for Games 2, 3, and 4?

If I were to really oversimplify some of these things, then I’d boil it down to this:

A few common pitfalls to avoid if you’re going for VC-studio financing:

The game pitch isn’t ambitious enough. Remember the J-curve. The only way the J-curve works is if the payoff at the end is potentially massive to warrant the investment at the beginning. As much as I love games like Hades or Hollow Knight or Slay the Spire, VCs are looking for $B outcomes so there has to be a story that leads to that. You can take inspiration from indie games (they’re actually some of the most fun games out there) but there has to be a business model that aligns with how VCs work (generally multiplayer + live-ops, sometimes with a UGC angle too).

Remember that when VCs are funding a studio, we’re not funding the game, we’re funding the company. This is an important distinction because the company has to evolve past a one-game studio into a multi-game publisher with an inherent distribution advantage through its own audience and platform.

The reason why publishers will invest in smaller premium games is that they have options to de-risk their investment: production milestones for the studio to hit, revenue share to recoup their capital outlay, and more involvement with the governance and management of the studio itself.

The team hasn’t proven enough by the Series A. Series A’s are really murky in this environment. Compared to traditional consumer Series As where it’s a product-market fit bet (e.g., this social app has strong DAU/MAU, month-on-month growth, and D30 retention and we believe the unit economics will work at scale), games studios often haven’t gotten to traction yet at this point. So VCs are forced to go off of more qualitative things like team velocity, production quality, genre thesis, systems design, combat feel, etc. We have to predict that this product will be a large outcome without traction and “invest in our own genius,” which is always dangerous. It’s always easier to bet on something that’s working.

So what can you do? In my personal opinion, the best thing that founders can do to increase their chances at a solid round are to be extremely disciplined about burn, have a strong thesis about the genre they’re going after, and execute against that vision as quickly as possible. Prove a lot, with a little. Build in public. Consistently test your game with players earlier on.

There isn't a unique insight. We’ve heard hundreds of pitches and so there’s a lot of genre mashups we’ve already seen, everything from Animal Crossing MMO to accessible Tarkov to Dark and Darker with guns. All of these are fine and dandy (and many could work!) but we want you to drill down to the nuts and bolts and tell us things we haven’t heard before. Find your edge!

League succeeded because of the unique insight on DOTA/DOTA2 being very popular mods with terrible distribution, and capitalized on a new F2P business model and jump-starting from the existing community

Valorant had the unique insight of a strong tac-shooter community that hadn't seen innovations in years, and combined that with more recent hero-based shooter metagame.

I have a few ideas for founders and investors that might increase the odds that the studio is more likely to ship the game while still retaining some of the necessary pressure of budget + production targets. I’d love any feedback on these as I’m just brainstorming, so feel free to email me if you have thoughts:

Larger seed rounds for more equity. One idea would be to raise larger seeds ($5M+) that give the startup more capital to get to a more fully formed product, but take more dilution early on (30%+, potentially co-led by two VCs). There are clear pros/cons to this one, since the founder will be taking on more dilution early but they would also have more money to work with in order to get the game to a solid second round. There’s an argument that the risk that early stage VCs take isn’t properly baked in for games, and so that should result in different deal structures.

Combo VC-publisher deals. The VC and publisher would work together to co-lead an equity + publishing deal at the Series A that will fully fund the game to launch with a marketing budget. This is similar to what the $31M Gardens deal had to fund their new cozy co-op game. The main advantage is to fully fund the game and de-risk downstream capital needs. The VC and publisher also serve to counterbalance each other, which generally will be better for the founder overall (better publishing terms, de-risked downstream capital).

Faster, leaner GTM. Lethal Company, Battlebit, Palworld, Among Us, and a slew of other viral hits from previously unknown developers who had unique insight into their genre show that there are other ways to create content besides the AAA studio model. I’d encourage founders to re-think how they might run prototyping, production, and GTM. Some ideas could be:

Outsource non-core development and find diamond in the rough talent internationally

Lean into emerging AI tools to quickly iterate on production (animation, SFX, VFX, voice, code, etc.)

Build communities earlier and share the development progress with them on Discord, Twitter, TikTok, and any social platform

Playtest, playtest, playtest

Pulling up revenue generation. This is basically the Kickstarter idea, or selling early access / founder packs. The main risk here is that you don’t deliver on the product to your players and you aren’t faithful to your promise. However, it can be a useful way after you’ve built a community to continue to service a loyal audience and get them invested in your success.

The games industry is at an inflection point. I believe that there will always be great gamemakers out there who are pushing the boundaries of play, but we need to make sure that the system is set up well to find these founders and ensure that they get a good shot at getting the capital they need to get the game to market. That’s why we built SPEEDRUN, to work with more founders building in games x tech and support them as they make their vision a reality.

Fully agree with the insight you provided on the UA moat... so critical that the moat is on the LTV component and not on the CPI component especially on mobile. With all the marketing research tools out there, CPI gets matched pretty quickly between two serious teams. LTV though has a real chance of remaining within the company's control. Publishers still focus on CPI as they should, because their timelines and expected outcomes are pretty different from VC timelines and outcomes.

" With games, you’re competing for consumer attention that’s split among apps, videos, music, and more. That’s why investors are always looking for differentiators with games: faster GTM, cheaper UA, network effects, platform plays, UGC lock-ins."

👆👆👆 just wanted to highlight this is a great distinction between VC vs Publishers as I've argued that TikTok or Netflix is as much competing against us as another competitor. So often in game studios you see a hyperfocus against competitors in the genre vs an understanding that it's about the attention economy.

Really great insights with the pitfalls and VC perspective... lots of food for thought.